News

September 26th, 2013 by admin

Now private companies can try to raise funds from the public at large.

By Antonio Regalado

During a “demo day” in Silicon Valley last August, entrepreneur Mattan Griffel took the stage with a well-practiced, carefully timed pitch.

“We teach people how to code, online, in one month,” said Griffel, adding meaningful pauses between the words. The startup he cofounded, One Month Rails, will “change the face of online education,” Griffel promised.

Such technology salesmanship used to be reserved for a select audience of angel investors, like those who attended the invitation-only Y Combinator event where Griffel’s video was filmed.

But starting Monday, Griffel’s pitch appeared on the Internet, next to a clickable blue button that says “Invest.” Buying into his startup is now almost as easy as purchasing a toaster on eBay.

“Crowd investing” is the idea that anyone should be able to invest easily in startup companies. That idea took a big step forward thanks to new federal regulations that allow startups, for the first time, to invite large swaths of the public to invest in them.

The new rules are part of the 2012 JOBS Act, a basket of regulatory changes that Silicon Valley lobbied for and that are meant to make it easier for small companies to raise money. The rule that took effect Monday reverses a longstanding ban on “general solicitation” or advertising risky securities to the public.

Under the new regulations, startups can advertise their shares anywhere—on billboards, on Facebook, via direct mail, e-mail lists, or via a dozen online crowd investing portals that have been set up to solicit and manage investments from the public at large.

Griffel’s company appears on Wefunder.com. The site, which was founded last year but became fully operational today, allows anyone to navigate through pitches from two dozen companies developing everything from small farms in shipping containers to new ways to transmit money overseas.

Crowd investing could ultimately have broad effects on what types of technology are able to win financial backing. In particular, it could lead to more gadgets that appeal to narrow markets or those that are developed by the maker movement (see “What Technologies Will Crowdfunding Create”). It might also create competition for traditional venture capitalists (see “Silicon Valley Dynasty Adapts to Fast-and-Cheap Startups”).

Mike Norman, president of Wefunder, says popular technologies that are highly “sharable” will generate the most interest. On Wefunder, for instance, a company called Terrafugia is developing a “flying car”—a plane that has retractable wings and can drive on highways. Most startups can’t yet rely on crowd investing to raise as much money as they need, however. Terrafugia, for instance, has already raised more than $10 million from conventional investors. For many companies, crowdfunding will instead be a way to reach out to hard-core fans and potential customers.

Carl Dietrich, Terrafugia’s CEO, called crowd investing “an interesting experiment to see what happens.” His company already has 83 different investors, many of whom chose to back flying cars because they believe such vehicles should exist and might increase people’s freedom. “What Wefunder is doing is providing the crowd an avenue for direct input into what the world should look like, and what kind of companies there should be.”

Wefunder’s website, with a menu of companies and short promotional videos, looks a lot like Kickstarter, the popular site where filmmakers, authors, and technology companies can raise donations for individual projects. That site has already spawned several technology companies, like Pebble, maker of a smart watch (see “A Smart Watch, Created by the Crowd, Debuts in Vegas” and “10 Breakthrough Technologies 2013”).

With crowd investing, however, people will actually be buying shares in new companies. For now, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which regulates financial markets, is limiting crowd investing to accredited investors, or people with $1 million in the bank or who earn more than $200,000 a year. However, the SEC is developing other regulations, due out next year, that would let any member of the public invest small sums in startups.

Some investors may hope to get in early on the next billion-dollar technology company, but the odds say most small investors will be losers. Since 1999, even professional venture capitalists have had dismal returns, barely above zero (see “The Narrowing Ambitions of Venture Capital”). And because individuals invest in fewer companies than professionals, the chance they will see their money again is even lower. “People should not be betting their retirements or kids’ education on startups,” Norman says.

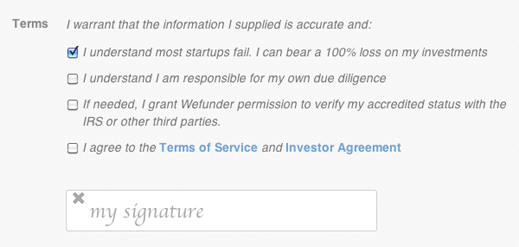

Registering to invest on Wefunder’s site takes only a minute or two. Users agree they meet the financial cutoffs, such as having an income of $200,000. Then a box appears, asking them to click on statements including “I understand most startups fail” and “I can bear a 100% loss on my investments.”

Due diligence: A sign-up screen at crowd investing site Wefunder cautions users that putting money behind startups is risky.

Due diligence: A sign-up screen at crowd investing site Wefunder cautions users that putting money behind startups is risky.

Crowd investors will have to judge startups and their technology based on very limited information. For each company, Wefunder offers a short “elevator pitch” and financial highlights summarized in three or four bullet points. There are stylized photos of company founders, whom investors can then “meet” by watching short personal statements, or visiting their LinkedIn pages.

While that seems like little to go on, it’s not unusual for early-stage investors to make quick decisions, Norman says. “Angel investors sit down for an hour, and then write a check,” he says. “At this stage of the company so many things are going to change that it’s really about the founders.”

According to CFIRA, a trade group, there are more than a dozen crowd investing sites in operation or being planned, including SecondMarket, Equitynet, SeedInvest, and OfferBoard. Details of how to buy shares vary between funding platforms. On Wefunder, up to 100 small investors will join a limited liability company, which will then make the actual investment in the startup. Wefunder, acting much as a venture capital firm would, manages the investment and collects 20 percent of any profits.

It’s still uncertain how big an impact crowd investing will have. The SEC is considering further rules, including requiring startups to track all their advertising, including every mention in the news media. That has some investors worried that crowd investing could flop. Investor Brad Feld, a partner at the Foundry Group, recently called the SEC’s additional rules “one scary mess that could undermine the whole thing.”